PROLOGUE

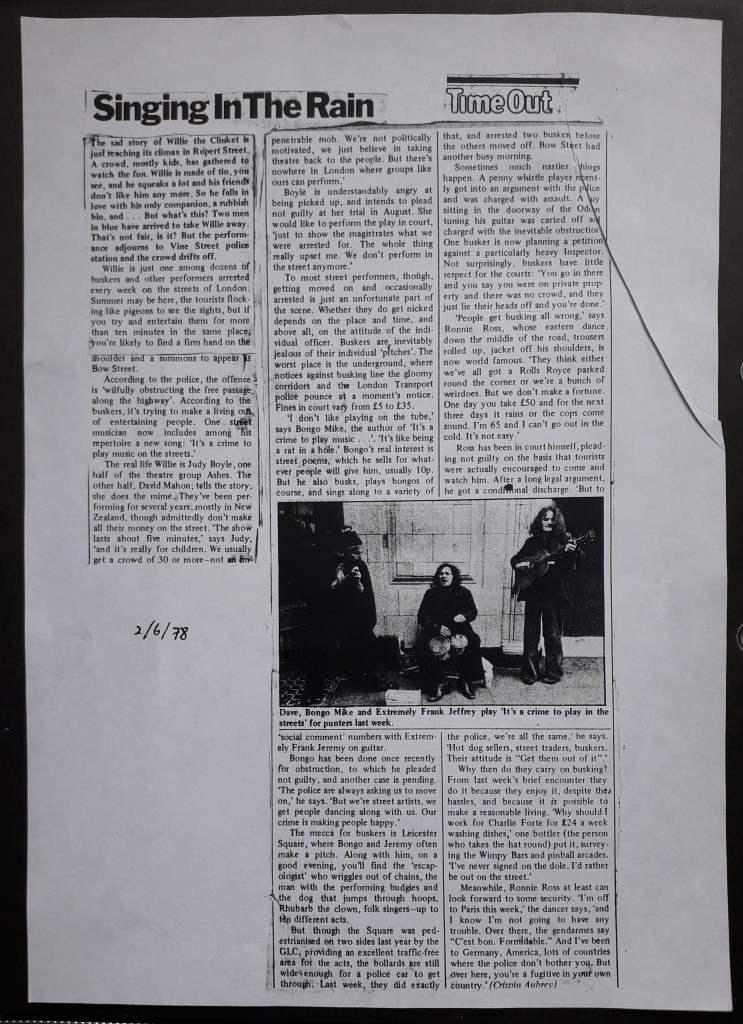

Right from the start of our busking partnership in Spring 1978, we – aka Bongo Mike and I – were unhappy about our situation as buskers in London generally, and in the West End in particular. After several months of being continually ordered by the police, for no apparent reason, to “move on”, and being then arrested and prosecuted if we resumed playing after they had gone – or even if we were simply rash enough to protest – we eventually reacted by contacting Time Out (in those days a fairly radical magazine) with the whole woeful story of the game of cat-and-mouse endured by buskers all over the capital.

Shortly after the article appeared we followed the recommendation of a Belgian visitor to London with whom we had got talking one day, during a break in our performance, and left these shores for Antwerp…. and beyond. For four years we were no more than occasional visitors back to the UK: NFA (no fixed abode), as the British police would so charmingly designate our status; or nomads, as we saw it, carrying with us, wherever we went, our musical instruments and a large army-surplus kit-bag.

Two places stood out as the only fixed points in our life – i.e. places where we knew we could simply turn up, no questions asked, no matter how low we had got, and just sleep, rest, recover, regroup, etc. These were Wädenswil, in the canton of Zurich, Switzerland, at the home of a journalist friend called Arthur Shappi; and Hotel Shar, in the Stara Charshiya district of Skopje, Yugoslavia.

Belgium had become the centre of our performing life; but Switzerland and/or Yugoslavia were our places of last refuge….

….and as for Britain, where we had now no income or base, it was just a place to which we could make occasional nostalgic forays of one or two days duration (or slightly longer if we could connect with someone we used to know, or find an empty building to squat in, such as the deserted houses on Railton Road in the aftermath of the Brixton riots of 1981).

FOOTHOLD

But all this was to change in 1982. On a train journey early that year from Leuven (the centre of our cafe musician business) to Hasselt (a town in eastern Belgium where we had many times performed), the train had developed an electrical fault and was kept stationary between stops for maybe half an hour. Sitting there with instruments primed and ready to play in the cafes of Hasselt, in a carriage full of people bored and increasingly annoyed at the delay…well, wouldn’t you have decided to just break into song for the fellow passengers, and go round with the hat? It was, after all, not that different from what we would eventually be doing in the restaurants and cafes in Hasselt – if we were ever going to get there!

So we did it, right there, on the train.

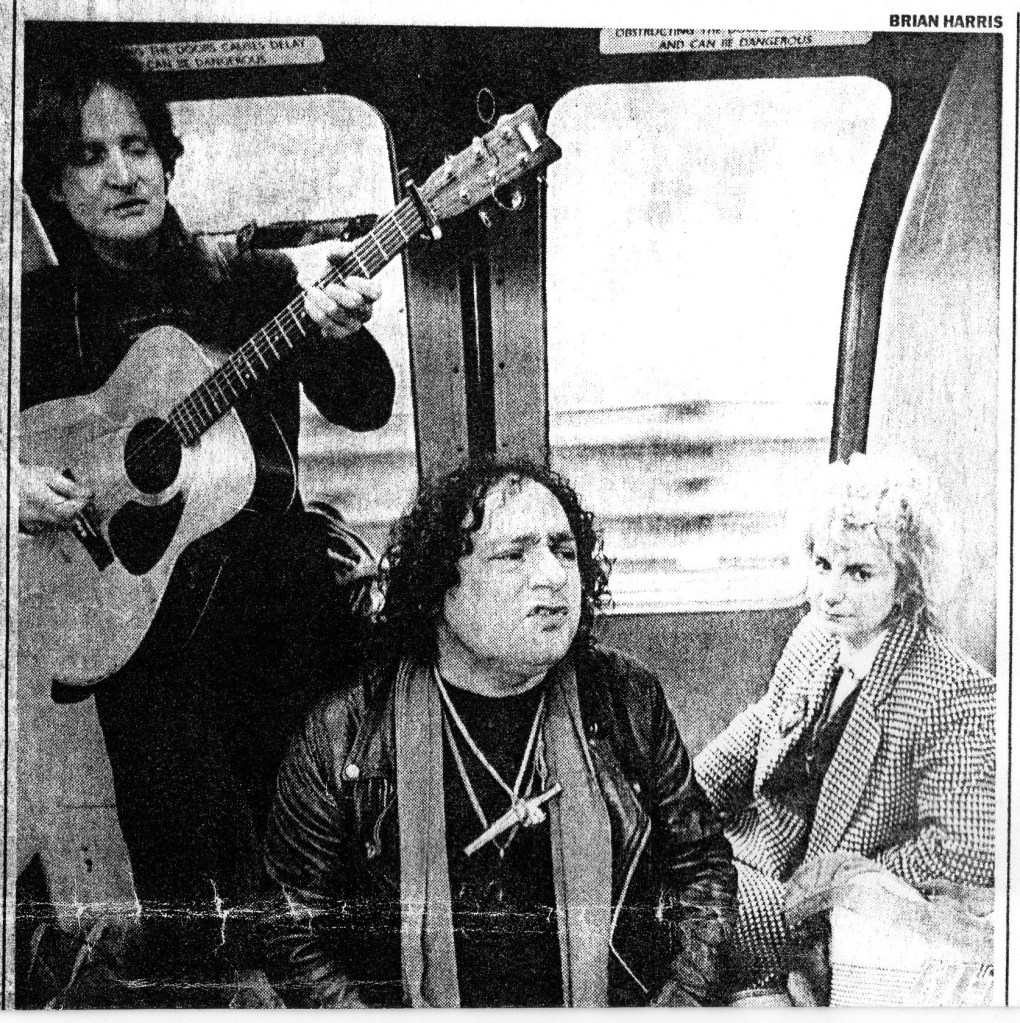

Then on a brief return to London in Spring, shortly afterwards, we got talking in a cafe near the Oval to a friend of a friend who invited us to stay temporarily in a spare room in a housing co-op nearby….and, well, the respite thus gained did allow time for an idea to cross our minds, that some tube lines, being situated above ground rather than underground, might be quite suitable for a repeat of what we had done recently on the Belgian train.

But controversy struck from the very beginning. On the first train carriage we tried, a gentleman announcing himself as an employee of the tube started shouting at us and ordered us to stop. Seeing discretion as the better part of valour, we got off the train, boarded the next one, and tried again; this time we were more lucky, and thus emboldened we continued for some time, playing two or three songs on each carriage before taking the hat round, in the time-honoured manner of gipsy-style players – such as we had indeed become on the other side of the English Channel – or indeed, of good old British buskers.

We experimented on various lines with varying degrees of success for a week or so, before returning to Belgium. Significantly, the level of official interference was sufficiently low for there to be an apparently viable modus vivendi in it.

And after as momentous an event in our lives as that had been, it was – I suppose – only a matter of time before we would relocate back to London.

In the event, it took about six months.

LEGAL CONVERSATION

But in the intervening Summer in Leuven we met by chance – while performing to a terraced street cafe – a law professor at the University there, called Raf Geraert. We were explaining to him some extremely distressing aspects of our situation – specifically, the insecurity stemming from the lack of residence rights in Belgium and the continent broadly, and this coupled with the lack of right to perform in public places (to put the case mildly) in UK. In this connection, I present here a relevant poem of Mike’s:

M. Geraert came up with no specific suggestions on this occasion, as I remember, but his grasp of what we were talking about, which few people in those days took at all seriously, impressed us, and opened a new chapter in our minds – if nowhere else, at that stage.

LONDON AGAIN

So, anyway, come Autumn 1982, with new confidence, probably derived from the fact of having glimpsed, however dimly, a way forward, both at a practical and a conceptual level, we came back to London determined this time to find a place to stay, and ran into some luck – a chance meeting in Barclay’s all-night cafe in Whitehall led us to a house in Elephant and Castle where lived a bottler for one or two of the West End buskers (a bottler is the person who takes the hat round when a crowd gathers), who seemed happy for us to sleep there for a while, making it possible for us to explore the possibilities of our new job (busking on trains), start to re-orientate ourselves to the situation in London, and hopefully reconnect with friends from the past.

There was a largish number of musicians who performed underground at Tube stations, in passageways or sometimes at the foot of escalators. This was, of course, illegal – posters announcing the fact were placed everywhere on the walls, and there was a permanent risk of being stopped by members of staff or Transport Police, and further of being charged with a bye-law offence and receiving a fine. This hadn’t appealed to Mike and me in 1978 when we first started playing together, and it still didn’t.

In parallel with this there was, performing in streets mainly in and around the West End, a certain community of more traditional buskers, most of whom we knew from our time in London in the 70’s. There’s was also a fugitive kind of existence, in and out of police stations and Magistrates Courts – precisely what we had left the country to avoid; and even if there could be periods when the heat seemed to be off, the threat was always there.

And lastly, there was just one person who was already playing on the trains – of the Piccadilly Line: a lady called Elsa, who played guitar and sang folk songs with a beautiful and powerful voice, her boyfriend always somewhere nearby, mingling discreetly with the passengers in case of trouble.

We took to performing on trains like ducks to water, concentrating in the early days on the branch of the Piccadilly Line which went to and from Heathrow Airport.

Our bottler friend in Elephant and Castle would be visited at all hours of the day and night by other members of the Soho fraternity: Scotty the one-man-band; Roy “Little Legs”, at 4′ 2″ probably the shortest busker you would run into; the Earl of Mustard, aka Norman Norris, tap dancer “extraordinaire”, self-styled “King of the Buskers” and even, in a considerable flight of fancy, “King of the Squatters” (“everyone who shares a squat with me ends up with a council flat”); and – on a brief visit to London from his then home in Copenhagen – Don Partridge, of “Rosie” fame.

At some point in December we were surprised to see – quite by accident – an article in The Times featuring an interview with a gentleman called Allan Bernard who was running an agency which apparently represented the interests of, and found occasional “professional” work for, a number of the more traditional type of buskers I’ve just been talking about. He gave an interesting appraisal – which echoed our views precisely – of the uselessness of licensed situations such as existed in Covent Garden at the time:

“The Covent Garden system is fine for young music and drama students, guitar strummers and newcomers generally. But it has developed into no more than open-air concerts with, in some cases, benches provided for the audience to sit and watch at certain set times. The art of busking is not just playing an instrument, juggling or tumbling, it is also about how to work a street corner or pavement and the ability to relate very rapidly with a constantly changing audience…”

But sadly the article itself said nothing about the real life situation of constant harassment and arrests for those who practised the art of busking thus described, and was rounded off with an absurd reference to what the journalist called “a renaissance of street life in London”, sacrificing – as it seemed to us – what working buskers knew to be the truth, in favour of a facile up-beat conclusion.

We duly contacted the journalist, Mr Tony Samstag, and explained our points to him. He was reasonable enough to take on board what we said, and on January 4 1983, some three weeks later, we were very happy to see the following article in the same paper:

What we were not expecting, was that many (though certainly not all) of the buskers around at that time would actually be quite hostile to us, and would not support our stand at all.

Nevertheless our blood was up, and though – sadly – we didn’t get the asylum in Belgium, we had a further conversation over there with our law professor friend (see above), who recommended that we try our luck with the European Court of Human Rights.

The progress of our – ultimately unsuccessful – application at the ECHR is detailed in an earlier post, “The Casebook of Bongo Mike and Extremely Frank Jeremy (1)”.

But there were further actions in UK!…..(to be continued.)