Travelling from one pitch to another, making friends, being offered hospitality in many towns – our lives were ruled by the twin necessities of finding places to perform, and finding places to get a night’s sleep.

These keys fitted locks of all different addresses in many countries. Some of them unlock doors in the memory too.

Like this one for example – a hotel room-key we accidentally walked off with.

It was 1980 ( I think, though it could have been ’79). We were having our customary late Summer break in the Balkans, and decided that, rather than spend the whole time in Macedonia, we would make a tour round nearby Kosovo – similarly, at that time, a part of the now-disbanded Yugoslavia, being a designated “autonomous region” of Serbia.

We stayed some nights privatno – that is to say, in unofficial lodgings – in Pristina, the main city, and then struck out for Peć (pronounced Petch), a city surrounded by mountains, which we had been told was very beautiful.

Hitch-hiking was rather slow, and by evening we had still only reached Kosovska Mitrovica, where we broke the journey to get a meal in the self-service restaurant (every town of any size in Yugoslavia boasted a state-owned, low-priced, self-service restaurant) before returning to the road and attempting to resume the journey. Lifts were still not forthcoming, and we got into conversation with a visiting student from Syria who happened to walk past where we were standing, and who offered to put us up for the night in a room he rented from an Albanian family living nearby.

The following day we made it to Peć, which was – as expected – very picturesque, and we settled in for the night at the local campsite, just outside the town, which also had a few rooms. There was a band playing in the evening, Albanian dance music – or “new folk”, as the pop music with a local flavour was generally called. However the band, as was later explained to us, performed some songs which were possibly expressive of Albanian nationalist aspirations, the police appeared, and the fiesta was dispersed.

I want to stress that at this time Mike and I knew nothing of nationalist movements within Yugoslavia – we had not the slightest interest in local Balkan politics, being quite fascinated by the glimpse we were getting of life in a communist society, co-existing as it did in Macedonia (and to some extent in Kosovo) with the remnants of five hundred years of Turkish occupation. Moreover the members of the band, with whom we spent some time after the closing down of the evening’s entertainment, were talking of their interest in the music of Deep Purple and Santana rather than in anti-government sedition. As professional musicians, they had merely been carrying out what is expected of professional musicians the world over, aka playing what the guests ask them to play.

And so onwards the next day, with Prizren as our objective – described to us by all and sundry as an interesting town with many remaining buildings from the Turkish era, although little-known in the west, except perhaps today as the home city – as I have heard – of the family of singer Dua Lipa. Our bad luck with the hitch-hiking persisted, and by the early evening we were happy to accept a lift from the only car that had stopped all day, even though it would take us no further than Đjakovica, a small town halfway to Prizren. The two young men in the car spoke no English and we no Albanian, or – at that time – anything much more than a few words of Macedonian, so conversation was difficult.

Shortly before we arrived in Đjakovica a police car overtook us and signaled to the driver to stop. After a brief conversation with the driver and his friend, the two policemen ordered Mike and me to step out of the vehicle we had been in, beckoned to the young men to move off and to us to get into the police car, and then drove us to a nearby police station. There we were questioned about what we were doing in Yugoslavia, how much money we had etc, our bags were opened and searched, and a sheaf of illustrated poems about street-life in London, written by Mike, seized upon and apparently confiscated.

We were given the option either to spend the night in the cells, or to leave our passports with the police and spend the night in a hotel. We opted for the latter and walked into the town, somewhat bemused by the turn of events – although, looking back now, it was not so very different from things that were happening closer to home in those days, except that the fear factor maybe increased with the greater cultural distance.

And so we arrived at the Hotel Pastrik, in Đjakovica, recommended – as I remember – by the Police for its reasonable prices. The receptionist understood the situation; after an uneasy night’s sleep we dressed and headed for the Post Office, where we had been informed we could find a long distance-telephone, which we needed in order to put into effect the plan we had formed to call up the British Consulate in Belgrade There was a considerable queue, and as our impatience boiled over we started to get an unusual sensation – for us, at least – of being like visitors from another planet. Some shouting took place.

Eventually we got our phone, and were able to reach the British Consulate, where a typically polite, phlegmatic English person listened to our story and undertook to speak on our behalf to a contact in the Belgrade Police, whom he thought could straighten the matter out for us.

He advised us to call back in about half an hour, and after an anxious wait we spoke to him again. He had – as he had promised – sorted it out; we were to go back to the Police Station, where our passports and Mike’s poems would be returned to us. Whatever the reality, there had clearly been a decision to call the incident a misunderstanding: there were, one could easily suppose, not many foreign travellers of any description who visited Đjakovica, let alone two dangerously long-haired guitar-carrying scruffs like us.

Anyway, thus re-assured we attempted to make our peace with the people around us in the Post Office queue, at whom we had not long ago been exploding in frustration, and then made our way back to the Police Station. We were met at the street entrance by an officer who formally handed us our possessions and gave a kind of salute, for which we thanked him, before going on our way – only to find, once safely en route to Prizren (on a bus this time), that we had made off with our door key from the Hotel Pastrik…….

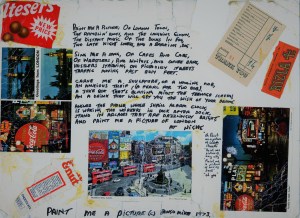

The poem “Paint Me A Picture” exhibited above, one of those which had excited the Đjakovica police’s suspicions about us, was also (along with the other poems in the series) a song lyric. Some ten years after the events related here, we recorded the song in Skopje, with a Macedonian arranger/kerboardist called Vlatko Kaevski.

Ten years later still, we became friends with an Albanian language singer from Skopje called Eroll Jakupi. This below is a video of him performing one of his own songs, QindperQind (or “One Hundred Per Cent”, in English), at a song festival called Polifest, in Pristina in 2003, where he won the gold award for best song that year.