Buskaction was the first, the original campaigning website concerning itself solely with buskers’ rights. It is still reachable at its original web address bak.spc.org/buskaction but we have not updated it since 2013 – that being the year when Bongo Mike became permanently bed-bound and I became his principal carer, and we decided it was the right moment to let the baton pass on to others.

So the names and faces of campaigners doing stuff may have changed; and I am aware of some local improvements for buskers, made by enlightened authorities, which give me hope that our energies weren’t completely wasted…. but then the legal battle, for us, was only ever a first step in the struggle to get busking seen as a type of art in its own right.

Buskaction went online in 1997 when James Stevens, a forward-thinking philanthropist from the then fast-expanding world of cyber-culture, offered us the chance to create our own space on the worldwide web, from which to co-ordinate the ongoing struggle for a better deal for buskers – well, worldwide!

We had of course been single-handedly fighting our corner in the UK through the British and European courts of law – and generating much publicity for the cause – for the previous fifteen years [see Casebook (1) and Casebook (2)], but had in 1996 joined forces with another group of buskers from the tube, who called themselves the London Public Entertainers Collective, and who had shortly beforehand followed our earlier lead in taking the path of legal action themselves – contesting busking prosecutions and generating further publicity on their own account.

We went with some members of this group to James Stevens’ Cyberlounge – Backspace – in Clink Street SE1, and there we constructed, with James’s enormous and patient help, the first few simple pages of bak.spc.org/buskaction , including as a special feature the “world premier” of the music video of our protest song “Don’t Know Why”, embedded in the site with Quicktime – YouTube still being eight years away!

BBC Radio 1 Newsbeat attended the launch party for Buskaction, in March 1997.

Then on 22nd Oct 1998 we launched our CD protest single at the Vibe Bar in Brick Lane. The record contained songs of ours, protesting against limitations of public place performances, including “Don’t Know Why” and “Its A Crime To Play Music in the Streets”. Both BBC and ITV local news ran the story announcing the release of this protest single, screening excerpts from the music video of “Don’t Know Why”.

Within a short while, both London Underground and Westminster City Council announced plans for licensing performances on the tube and in the streets of London, having somehow simultaneously decided that busking could make a contribution to the colour of the city, whereas they had both up till then treated it as an unwanted nuisance. Maybe they saw licensing as their best (or indeed last) hope for controlling things, now that the time-honoured practice of leaving it to the police was gettng a bad name; and maybe they were frightened by a ruling in the House of Lords at about the same time, overturning a prosecution of demonstrators at Stonehenge, and pronouncing crucially that “the law today should recognise that the public highway was a public place, on which all manner of reasonable activities might go on”.

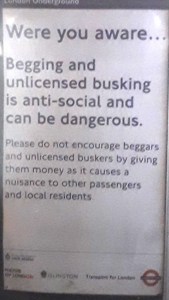

But whatever their arcane thinking may have been, certainly in neither case – tube or street – had they made any attempt to canvas opinion from regular buskers as to what sort of arrangements would or wouldn’t work to bring about an end to the official bullying and harassment suffered for so long by street and tube performers. Both organisations put forward ill-thought-out, non-consensual, top-down schemes which, far from improving life for performers, threatened to make it even worse: by failing to incorporate the ad hoc, freewheeling character of the busking phenomenon; by breaking up the informal arrangements which would spring up from time to time and from place to place between officialdom and “buskerdom”; and furthermore, by starting to give credence to a new concept of “unlicensed busking” as an automatic offence, on a par with begging.

This poster which appeared in a subway near to Old Street tube station, in London, some time after the advent of the licensing philosophy, tells its own story. Added to which, a prosecution mounted as late as 2009 against London busker Bernard Pierre, which attracted some interest from the press, threatened to give this dangerous idea some legal validity.

Fortunately the danger of some kind of ugly low-level precedent being set, whereby an “unlicensed” busker could be considereded equivalent to a beggar, was averted by virtue of Bernard’s successful appeal against conviction.

Others will doubtless be more up to the minute than I am with busking politics in this post-licensing schemes world. Schemes put on the table by Camden and Westminster Councils have been hotly contested. I would think the main basis for hope on the street – despite the shaky start described – is that many councils have simply not bothered with setting up schemes of the type envisaged by Westminster; and that further, as the years have gone by, the Police have in many areas backed off anyway, apparently happy to leave it to council officials to boss around or not boss around street musicians, as the case may be.. Sadly, however, that’s not to say that vindictive anti-busker attitudes and/or regulations are simply a thing of the past.

As I mentioned above, I have – when it comes to street playing – largely hung up my boots; though not without a brief re-incarnation in 2021/22 as a one man band, which I undertook partly to experience the feeling of “going it alone” (albeit I was often accompanied by blues harpist Mal Collins), and partly to celebrate the partial decriminalisation of busking that had been achieved after so many years. I did have the enormous satisfaction of being able to perform with impunity outside Earls Court tube station, a spot from where Bongo Mike and I had been comprehensively bundled off by the Kensington Police some forty years previously.

Nor, in fact, am I completely ruling out further “nostalgia” busking pitches in the future, wherever my remaining years may take me. You just never know what the future might bring. But this blog is, unlike the avowedly campaigning site Buskaction, primarily the story of a personal journey.

“This is Earls Court. Just outside the tube station. I’m singing a song called Midnight Special. It’s a song about being released from prison. I see it as quite a religious song. When Bongo Mike and I started busking in London, this was one of the first pitches we found – playing, well, almost where I’m playing now. But the trouble was, in those days you could only last for about twenty minutes (or maybe slightly longer if you were lucky). The police would come along, and say, “Just moving on were we”; or some kind of friendly greeting like that we used to get. And after a while of that it was getting very difficult to co-exist with all that, and so we went over to the continent, I’m talking about 1978, and for the next thirty years we spent a large part of our time on the continent – as we saw it, in exile, really. But we used to come back of course, and while we were back here we used to try and fight against the situation in any ways that we could. We took quite a lot of court cases and got quite a lot of publicity, in fact, for those court cases, and in the end – probably more the publicity than the court cases – actually started to have an effect because it was rather bad publicity for the set up here. And round the turn of the century – around that time – a lot of changes started to happen. Now change, it can be for the good and it can be for the bad, and where it was for the bad was that you got all these awful licensing schemes coming in – on the tube, and lots of towns, and boroughs in London started all this licensing – which wasn’t too good. But the good thing was that it was sort of taken out of the hands of the police, and the way it was going to be handled was put in the hands of the local governments, wherever. Well as time has passed, since it all started, the attitude has started to mellow quite a lot, and busking in the street is in many ways a thing that you can do now without too many of those type of problems. So I sing this song now with a sense of, well, triumph really, ’cause…..we got out of prison.”